Colors of a flag. The Hinomaru according to artists

The Hinomaru, or “circle of the sun”, is a universally recognized symbol of Japan, considered by many something more than a national flag. In the history of Japan, it has been used by many individuals and institutions to represent their power over an often actually very divided territory. From its Shinto roots of the sun image and its association with the goddess Amaterasu, to its use during the wars between daimyō, to the Tokugawa shogunate that started using it as an emblem against foreign powers. And finally, more recently, as the cruelly evocative crest of an imperialist nation. But it wasn’t only the authorities, warriors and noblemen who appropriated the flag during Japan’s long history. For example, artists and common people have reclaimed, deformed, or utilized the famous red circle in personal ways, even depriving it of its initial meaning and bestowing upon it a new aura and a renewal potential.

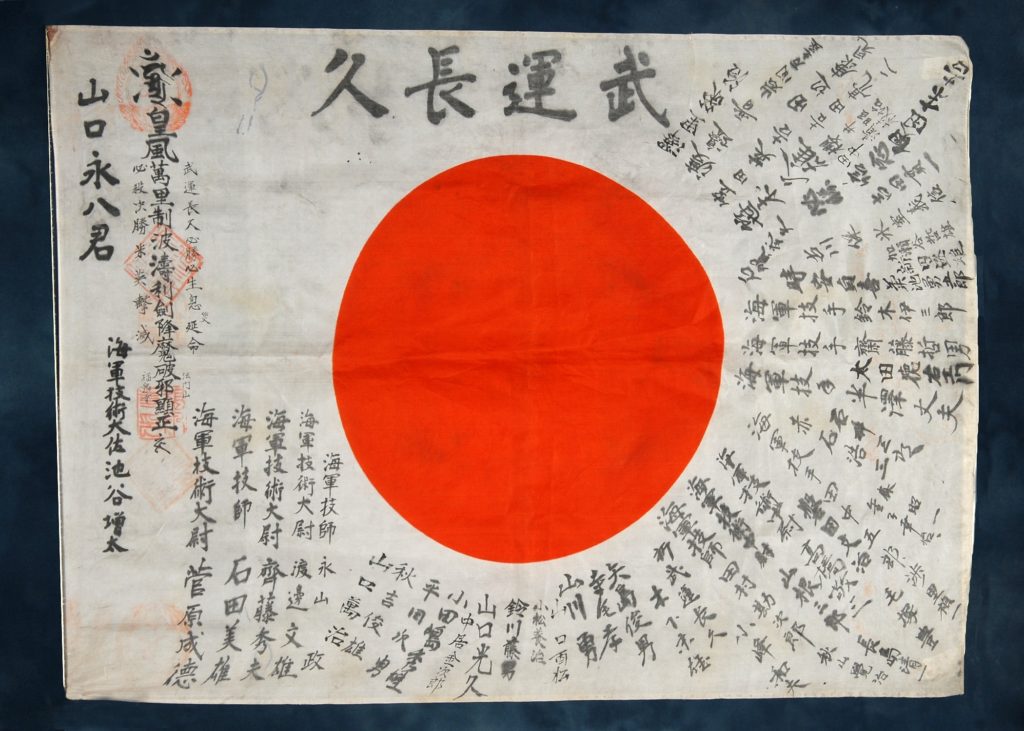

A practice called “yosegaki Hinomaru”

Although very much a testament of the fidelity to the nation and its ideals, the type of flag called yosegaki Hinomaru still represents a very personal practice. Yosegaki means “collection of writings”: Japanese soldiers, particularly during the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945), would receive a flag covered in signatures and various writings before their deployment. They were good luck messages from relatives, friends, and neighbors written all over the flag, but always avoiding the central circle. Thanks to it the soldiers were supposed to feel supported and encouraged during their service, but this personalized effigy supposedly had a more incisive and real power. Curiously enough, the prayers worked as a kind of propitiatory formula that would help the soldier as he was vulnerable and far from his country. All he had to do was unfold the flag, often together with his companions, and look at the writings left for him to unleash its protection.

This type of object was quite popular even during World War II, and it remains to this day an interesting case of appropriation of a national banner, making it something quite private and close to the person’s heart. It was probably a useful emotional tool in times of discouragement, when even fervent patriotism wouldn’t suffice. To feel his family closer and his hope revived, the disconsolate fighter could rely on a very personal object, instead of the colder, more detached and impersonal traditional flag.

Yukinori Yanagi’s giant flags

The current appearance of the Japanese flag has been officially established in 1999, but the recognizable red dot on a white background had been associated for centuries with Japan. It is truly almost a didascalic representation of a scorching sun, and an allegory of the long-awaited destiny of the country. Moreover, it is a charged icon that can still evoke the suffocating control through the propaganda and subjugation of the XIX and XX century. Even more frightfully poignant is the kyokujitsuki, the flag of the sixteen-rayed sun (or the Rising-Sun flag). Yukinori Yanagi has utilized both flags in its installation Hinomaru Illumination. Essentially, it consists of a gigantic neon flag that changes from a Hinomaru to a kyokujitsuki. In one version an array of haniwa, terracotta figurines found in ancient tombs, appear to be staring and saluting the flag, inundated by the light that it emanates. On another occasion, Yanagi put the installation in front of a shallow pool that reflected its glow throughout the different phases, presenting finally the viewer with a black sun, a lethal solar eclipse. The observer is taken on a journey to the ups and downs of the Japanese ideal and its troubled history.

Another instance in which he has included the famous red circle in his oeuvre is Banzai corner (1991): 349 Ultraman figurines are arranged methodically to form a red circle in the reflection of a big mirror. Just as the haniwa did in the previous work, the statuettes recall a feeling of community and group mentality, with their obsessive repetition. Still yet, with a chronological shift from the first work, this time Yanagi is not so much referencing the last century’s regime as the contemporary need for constant connection, consumerism, and the multiplication of identical habits and identities. In his hands, the kyokujitsuki has taken an unprecedented vulnerability. Indeed, it is almost mocked for its exhibitionism and associated with the more trivial, pop culture icons from a TV show. On the other hand, the title seems to still hold on to a sinister past.

Kikuji Kawada’s iconic picture

Another way artists have been able to shed a new light on the Hinomaru has been through their unique photographic gaze. Kikuji Kawada took a memorable picture of the flag laying on the ground, crumpled and crinkled by the boots of students protesting against the Security Treaty in the ’60s. It’s included in the book Chizu (The Map) a collection of pictures of abandoned architectures, urban waste, and the remainders of technologies in a postwar wasteland (1960-1965). He walked through the devasted city streets and the Hiroshima Atomic Bomb Dome, seeing beauty in desperation and almost accidentally documenting a pivotal historical moment. Indeed, he has been quoted as saying “What’s fearful is beautiful”.

The flag is flat against the floor and deformed, its two-dimensional appearance bordering abstraction. Certainly, the metaphorical implications of a tormented flag are transparent enough. What is really intriguing about the image is Kawada’s choice of including it in his collection between military facilities, ammunition, and a distressed Lucky Strike package. Consequently, the circle of the sun becomes then yet another token of the American occupation, of the postwar crisis and the chronic instability of Japan still perceivable in the tense atmosphere of the ’60s.

Hinomaru and Identity in Mao Ishikawa’s work

The Hinomaru, despite its intent of providing a nation-wide identity and sense of belonging to the Japanese people, is also a very divisive symbol. Population traditionally considered different from (and less than) the average Japanese citizen, such as burakumin, Ainu and Okinawans, often saw in the flag an oppressive and intimidating remainder of their secondary role in society. The Rising-Sun flag became a known synonym of colonialism and oppression for the people of the countries in the Pacific. Even today, it is considered indelicate to display it in public in many south-eastern nations and it’s heavily discouraged by the Chinese authorities.

The photographer Mao Ishikawa brought to life the project Here’s What the Japanese Flag Means to Me in order to explore the relationship between the flag and many different kinds of people. She was born in Okinawa and is therefore well aware of what its inhabitants had to endure during the American occupation well into the ‘70s. It seems that the Okinawans were not Japanese enough to benefit from the protection of their homeland. This only added to centuries of mistreatment by the Japanese mainland. Who are the Japanese people? Who are the Okinawans? Do they belong to Japan? What does the Hinomaru mean to them? And to Asian people? Ishikawa photographed her subjects while they were interacting in some capacity with the flag. Sometimes it was an official one, other times they had simply let drip some red paint onto a white sheet in a vaguely circular shape. Everyone seemed to answer these questions in their own way: some of them trampled on it, some used it as a sort of hood, sometimes they would cover themselves like with a blanket. In contrast, some are photographed near it, but seem to ignore its presence like a mere coincidence.

The project took place between 1993 and 2011, culminated with a book, and has led its author even out of Japan. Especially abroad, she was able to collect moving testimonies about identity and the constant struggle of individuals against insurmountable and unfathomable powers and their symbols. Even Ishikawa herself gives her sure answer with a self-portrait and the words

“I am not a Japanese, but an Okinawan. And I will live proudly as an Okinawan, forever.”